Adams (b. 1937) is an American photographer who grew up in New Jersey, Colorado, and Wisconsin. As a young English professor in Colorado, he learned photography during his summers off, turning his camera primarily to the nature and architecture of the prairie. In 1970, he began to publish his photographs in a series of books, ranging in subjects, but always focused on the topography of the American West — from its untamed landscapes to its suburban sprawl. He still works as a photographer and enjoys recognition as one of the nation’s leading practitioners of the art.

It is tempting to reduce Adams’ work to a political statement or activism, but when you begin to look at the photos, you realize that Adams, before anything else, is asking us to pause, take note, and hopefully to cherish. His work captures a quiet beauty in the landscape — a beauty that does not impose itself on us or ask anything in return. In 2021, he stated:

There are at least two kinds of silence that define us. One is the eloquent silence of the world as we were given it — the silence of light and beauty, the silence that holds a promise…there is also sometimes a dark silence within us, one that results from willful blindness and deafness. We struggle against it. What will America be? Will it accord with the stillness of sunlight?

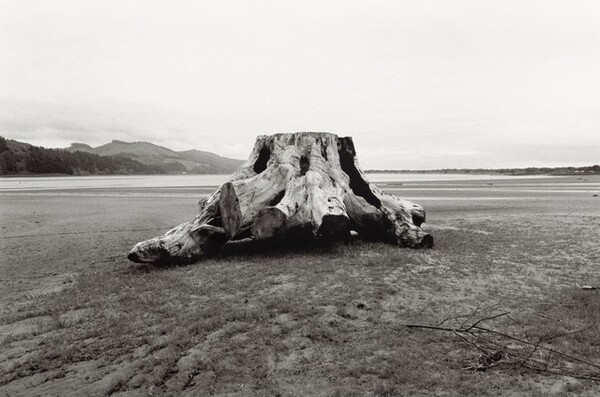

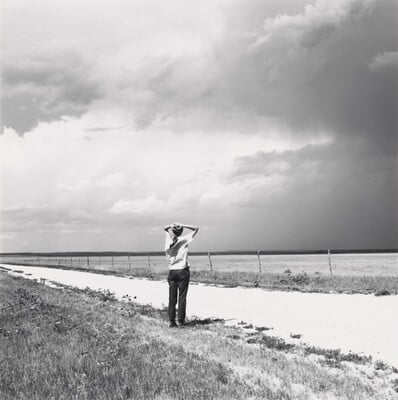

These are the questions that his photographs ask or beg us to consider. When you look at Weld County, Colorado, 1984, there is an expansive, wild beauty that draws you in. This same attraction is present in Rivers Edge, 2015, yet the starkness contains sadness and clear signs of loss. Both of these images, and really all of Adams’ work, are poetic in their care and respect for the subject they capture. The photos become almost a love letter to an incomparable lover, full of hope as well as tragedy.

While most of Adams’ work is usually “unpeopled,” free of human subjects, there is a series of works focusing specifically on the communities and housing developments that rapidly began popping up in the 1960s. It is impossible to ignore the anxiety and loneliness present in these subjects’ faces and the swaths of identical, crowded tract homes. In Adams’ words, “After people live awhile in a place to which they’ve laid waste, it gets to be easy to hate a great many things.” The same land that hummed with a quiet beauty now becomes almost menacing, and the people populating it become tragic figures.

In Robert Adams’ photography, we find the power of art and beauty to call us out of ourselves, causing us to listen and love. He is not only asking us to consider and care for what has been freely given, but to care for our own hearts amidst a culture that rapidly consumes and pushes forward without care for land or people. The beauty of a landscape is the beauty of a gift and when destroyed or mistreated, we too are left hurt and homeless.

Rachel Tanzi works at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. planning public programs and educational engagements.