The artless parody of higher education that passes for today’s university system seems perpetually engaged in the censorship of new ideas and important conversations. On extreme occasions, the redactor’s black marker extends to the classics themselves—such as when the classics faculty at Oxford University sought to remove Homer and Virgil from its curriculum. Eliminating these complex readings from the requirements was aimed at fixing “attainment gaps found between male and female candidates,” but thankfully the university decided that neither gender should be deprived of the Greco-Roman greats.

Hard censorship of this kind rarely reaches the epic poets. When it does, it makes headlines. But soft censorship—the deceptive editing and selective reporting of classical sources—is happening all the time. Sometimes it is done in support of ethno-political narratives, like English historian Mary Beard’s obsession with tuning the dials of skin pigmentation for historic populations. Sometimes there is a social agenda, like when classical philosophy professor Martha Nussbaum tried to argue that only Christians, and not ancient Greek pagans, placed restrictions on homosexual activity. And very often in the case of sacred texts, theological commitments incentivize the “translation” or outright elimination of inconvenient passages.

One interesting case of censoring the classics targeted a passage in the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius—a throwaway line nevertheless beloved by modern day homeschoolers. In this passage, he writes:

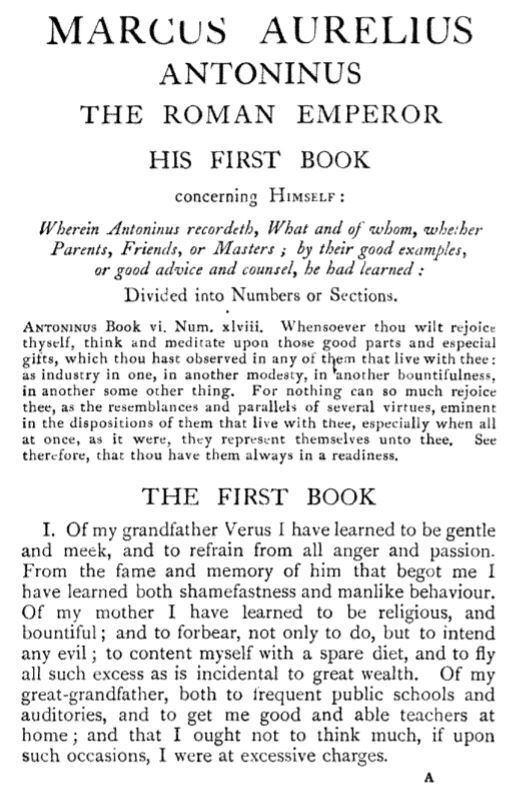

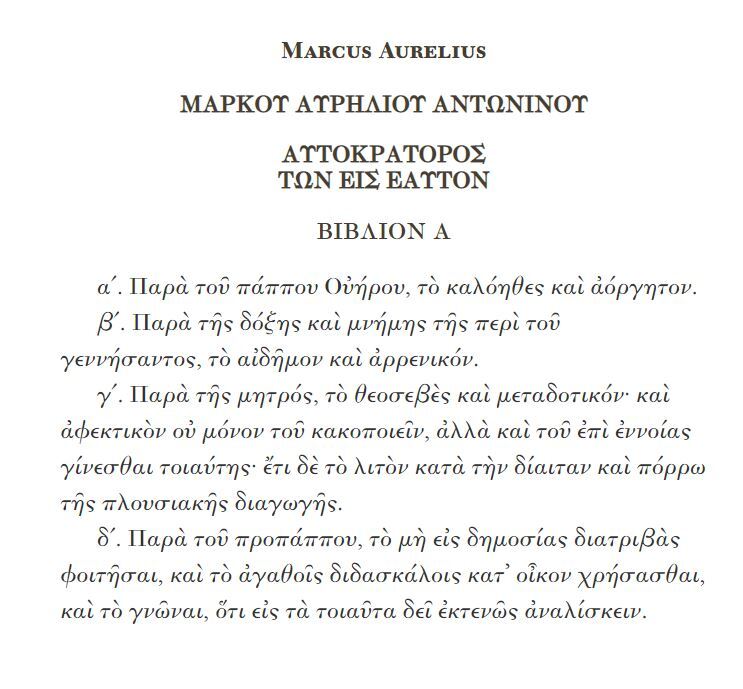

I have to thank my great-grandfather that I did not go to a public school, but had good masters at home, and learnt to know that one ought to spend liberally on such things.

This passage has been the target of censorship by various factions since the 17th century.

To understand why, it is first crucial to realize that there has been a debate on whether individual education was better than school since ancient times. Marcus Porcius Cato (234–149 BC), known as Cato the Elder, was a consummate “homeschool dad”—teaching his son law, history, rhetoric, music, and philosophy, taking him into battle with him, and organizing a physical education program to rival modern special forces training. He also taught his son how to appreciate the simple things in life, emphasizing that all statesmen should be farmers first, so they are connected to the land they help rule.

By contrast, Quintilian (AD 35-100) was a lawyer and schoolteacher who opened his own school for rhetoric in AD 69. In his book Institutio Oratoria, he outlines an aggressive argument against homeschooling and surreptitiously advertises for his own school, which he had been operating for at least 25 years. His arguments—children need socialization, parents are not qualified to teach, etc.—are still bandied around today.

Marcus Aurelius (AD 121-180) is a living rebuttal of this view, and remains centuries later the model homeschooled student. His governance was effective—Machiavelli named him the last of the “five good emperors”—but he also remained a philosopher who practiced Stoic detachment from worldly goods. The principles of education and life in his Meditations are still studied by modern day neo-stoics and all educated people.

The philosopher-king’s classic affirmation of home education, however, has long been controversial—and opponents of homeschooling have been out to censor it since the 17th century. Their method? An alternate “translation” of this text that has no basis in the original Greek.

In 1634, Greek-to-English translator Méric Causabon published a printing of the Meditations in which the famous homeschooling quote was subtly changed. See the corruption in his English version below, and compare with the original Greek—since that time, Causabon’s error has sneaked its way into various modern editions in English and other languages.

Méric Causabon English version and the original Greek

But why would Causabon edit out Marcus Aurelius’ support of homeschooling? For the same reason there are anti-homeschooling activists with an axe to grind in the 21st century. Causabon was a strict anti-Catholic in a time when England was widely barring Catholic practice and education.Only parents themselves were allowed to teach Catholicism to their children, and plans were in place to end even that practice by removing Catholic children from their families and placing them in Protestant homes. This is not to say that the censorship of Marcus Aurelius corresponded with a religious viewpoint—rather, it aligned with the totalitarian war on the right of parents to teach their children at home.

The classroom can be a path to opportunity or a tool of tyranny, depending on how responsive it is to parental choice and input. Similarly, the classics themselves can be tools of uncovering truth or concealing it. Despite centuries of soft censorship, Marcus Aurelius still speaks with an authoritative voice—and the battle over his words can teach us sharp lessons about education.

Andrew Cuff is Communications Director at Beck & Stone where he leads institutional clients in communications consulting and brand tactics. Created is his editorial project. He and his wife (also a writer) have made their home in Latrobe, PA with their four children.