“On the last day of class, I’ll bring a tiger in here. Then I’m going to make it disappear.”

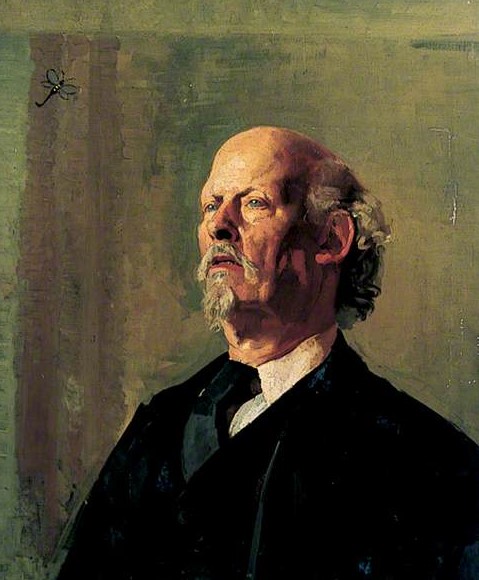

I never thought a course entitled Survey of Ancient History would feature a living jungle predator, but the septuagenarian in front of the room sounded dead serious. The man was pure gravitas: long white beard, wool blazer, briefcase. But his class only nominally covered ancient civilizations. Really, we were learning about history making—watching our teacher encounter humanity’s past as a macrocosm of his own—and following a methodology like nothing I’d seen.

I’ll never forget the day this professor unfurled a tattered Nazi flag from his podium at the start of class. Speaking in a loud voice, almost shouting, with one arm extended, he asked “Do you want to learn Herodotus?”

Eccentric professors are the spice of university life—and we’ve all had our share. Eccentricity is really synonymous with nonconformity, especially in terms of behavior. Somehow, despite the extreme personalities attached to it, the word has picked up no negative connotation. Everyone loves an eccentric—from a distance, at least—and for some reason, we treat their odd, often antisocial behavior as the adumbration of genius.

The eccentric professor archetype extends far beyond higher education. Stories abound of entire government agencies where all the real work is done by one extremely socially awkward spreadsheet wizard. There are tech startups where the “ideas man” does almost nothing except be able to dress himself and talk to both men and women—while the core of the company sits pajama-clad in sweaty basements across the world. In several Hollywood films, the lead actor is known for being so certifiably deranged, he actually thinks he is his character—and then wins an Oscar for his method acting.

Some might be tempted to think that eccentricity is merely a pretentious cover for mediocrity or negligence. Lawrence Olivier was a castmate of method actor Dustin Hoffman in the 1976 film Marathon Man. In one scene, Hoffmann’s character was supposed to be sleep-deprived, and the eccentric actor shared with Olivier that he had not slept for 72 hours to remain in character. “My dear boy,” Olivier replied in mock surprise, “why don’t you just try acting?”

Occasionally the eccentric is a try-hard, but assuming this is always the case becomes a prejudice that can blind us to some of the best characters in the story of life. For example: our eccentric history professor used to walk out of class if students used their phones while he was teaching. If a student cell phone left a pocket or came into his field of vision at any point, he would simply leave. It’s fair to say that professors today would kill for this privilege, and perhaps would come across as self-serving if they attempted it.

But, you never saw anyone texting in his classes.

He also insisted, as a stipulation of remaining emeritus, that the college hire a “body man” for him to guide him around campus and prevent him from running into trees. “Bad eyesight,” he claimed, but he also owned over 65,000 books, which I had the privilege of leafing through after his death, and discovered handwritten notes in nearly all of them. He could see very well, but perhaps trees were invisible to him until they were turned into paper.

The university system and other elite institutions have done their level best to kill eccentricity. Making unprofessional remarks or pursuing inappropriate rabbit trails in class can no longer be used as a way for professors to build rapport. Philip Roth’s The Human Stain (2000) chronicles the struggle session forced on a professor who casually asks if some absentees from his class are “spooks” (ghosts) who never attend. The truant students took his comments as racist, and inanity ensues.

We have all become familiar with this story in the two decades following Roth’s novel. Whether slips of the tongue, truth-telling, socially awkward moments, or merely grading fairly, even conventional academics are walking on eggshells, not to speak of the eccentrics. The great “institution within the institution”—the sage, the comic relief—is a dying breed.

Our history professor’s name, you’ll notice, has been redacted here out of respect and protection from posthumous cancellation. But there was nothing truly controversial about him. He owned a Nazi flag because it was given to him when he personally interviewed a member of the Nazi high command (following the methodology of Herodotus). He made risqué comments about Julia Roberts because, for him, the Pretty Woman actress served as a muse at least as important as Clio herself. His strangeness was his richness; his eccentricity was his value.

If elite institutions—universities, bureaucracies, laboratories, companies—will no longer protect eccentricity, I hope the rogues and outsiders and builders of new institutions can spare the time and energy to do so. Let the eccentric in the tower serve as the rallying point for building our earthworks. Yes, some of them are just awkward, oddballs, lunatics. But sometimes, without even meaning to, the eccentric gives the gift of life-changing genius.

Andrew Cuff is Communications Director at Beck & Stone where he leads institutional clients in communications consulting and brand tactics. Created is his editorial project. He and his wife (also a writer) have made their home in Latrobe, PA with their four children.