It’s impossible, as a European, to not be fascinated by the American flag. I currently have one in my living room. It’s a special one. Each time someone new walks into my Amsterdam apartment, they walk up to that flag to examine it. In a minute, I’ll tell you why.

The flag, for Europeans, is also a symbol of the magic spell the United States has placed on our imagination. In Italy, where I grew up, the fascination with America had already peaked among baby boomers, but their image of America was still largely that of the American dream. It was the last, diaphanous glint of the frontier.

My generation’s, on the other hand, was a new American mythos — the post-9/11 haze in which the frontier had finally dissolved, and behind which — still opaque — dim new lights were flashing, the muffled voices of forming media and technology empires were heard growing louder, luring in the European imagination with a new tune.

It was an Italian of the old generation, my design mentor, Massimo Vignelli, who was going to ignite my own fascination for America with his. As a boy, Massimo was among the Loreto Square crowd, jumping and groping about to see Mussolini's body hang lifeless from a gas station’s roof, and hear the stories of liberation by American soldiers. As an adult, even as a self-described Marxist who took educational trips to Russia, he loved the idea of the United States so much ("where the roof doesn't exist") that he and his wife Lella left Italy —where Massimo, who was only 26, was already lining up prestigious design assignments and Lella had just habilitated as a practicing architect — to cross the Atlantic for work in cutlery design at Towle Silversmiths and architectural design at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. They never left.

The two made their home in New York City, became citizens, and went on to become some of the most iconic designers of the 20th century. If you’ve ever commuted on the New York City subway, shopped at Bloomingdale’s, visited the National Parks, or taken an American Airlines flight before their disgraceful rebranding, you have seen their work. At the height of their fame, in 1985, they were presented with the first Presidential Design Award by Ronald Reagan.

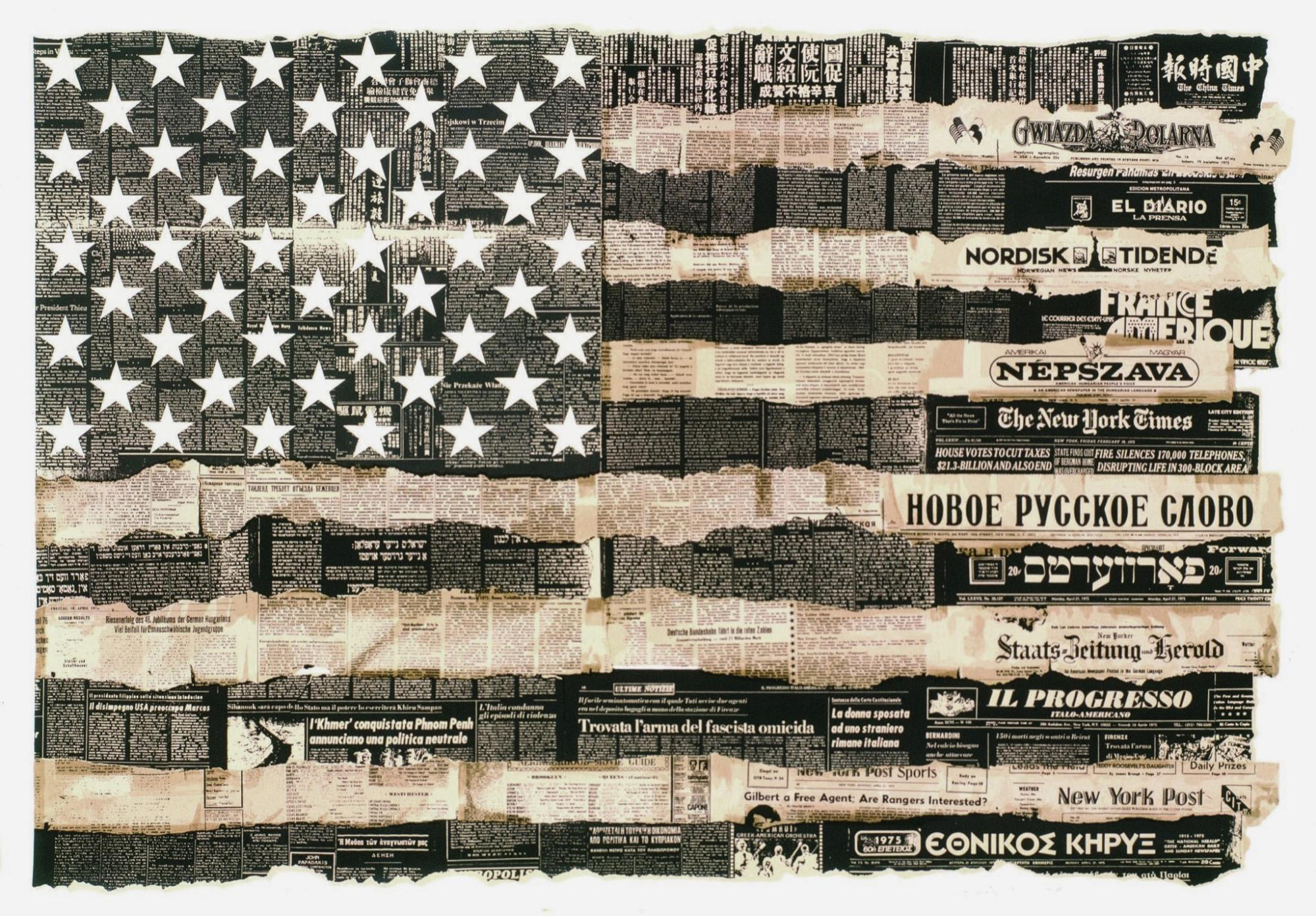

Then Massimo was asked to reinterpret the American flag. He wasn’t going to redesign the flag, of course — it was a celebratory flag of sorts. I have spoken about the American flag and its inherent charm to a European, but Massimo was no longer just a European — he was a European who had been living in America for over 20 years. He had now seen and lived the eclectic mixture of cultures and languages to which he and his wife, like so many others, contributed, and the idea immediately flashed in his mind: he would make an American flag out of this babelic diversity that somehow, almost magically, held together. He went out, bought every newspaper available in a language other than English (plus The New York Times), cut out stripes and white stars, and the below-pictured flag was made.

Massimo’s flag was enthusiastically received by the state committee until, at the very top, a Russian-speaking general noticed the Russian newspaper stripe — which was not to his liking. He asked Massimo to replace that stripe with a different one, and then the flag would be good to go. Massimo refused. The general retorted that if the stripe wasn’t going to be replaced, he would kill the whole project. Massimo thought this unacceptable — a direct violation of the very concept of the artwork — and didn’t cave. He kept the original, hung it in his office, and had 300 lithographs made of it, signed and numbered.

One of those 300 lithographs — as you’ve already guessed — is the flag that hangs framed in my living room. People walk up to it because I live in a place where all my friends speak a different native language; once they realize how the flag is made, they all want to check if one of the stripes features their own language.

That flag is the only piece of art I currently own. To me it’s a brilliant one, a memento of my mentor and of our mutual fascination (and sometimes, gripes) with America. But to an American, it should symbolize a lot more. What is interesting about Massimo’s concept and his refusal to concede to censorship, through the lens of contemporary American discourse, is that it can be read politically both ways. It’s either a refusal to the censorship of America’s diversity and multiculturalism, a negation of the “melting pot” spirit, or it’s a refusal to let power gag free speech. I like to think it is both—and fitting for that inherent tension in the American flag that seems inescapable from every angle, for the paradox that is so deeply woven into the fabric of the American idea that one is almost tempted to say: It makes sense because it makes no sense. It is true because it is contradictory. It is beautiful because it’s impossible.

Michael Klein is Creative Director at Beck & Stone where he leads the design team in its endeavors to connect ideas to culture. A native of Italy, he resides currently in the Netherlands.